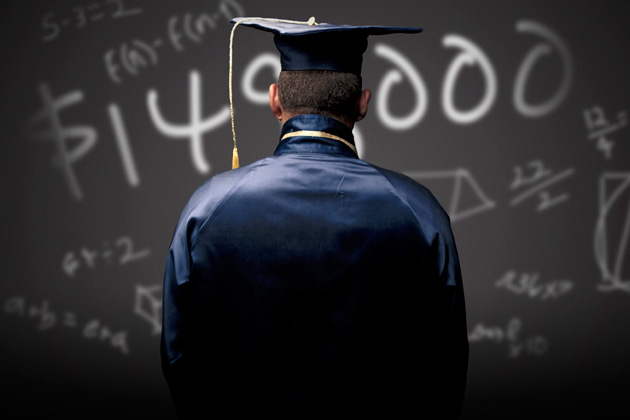

The problem of student loan debt in the United States has gone well beyond the point of crisis. Of the $1.2 trillion total dollars owed, $1 trillion is tied into federal student loans now hanging over the taxpayer’s heads. Overall student debt accounts for 6% of the entire national debt of $16.7 trillion dollars. Only U.S. mortgages account for a higher percentage.

As of 2013, the average graduate finds themselves $26,000 in debt as they leave campus and enter an uncertain job market. Students increasingly end up back in their parents’ homes, under-employed or not working at all, not paying taxes, and unable to pay back loans. As a result economists warn the housing market could end up as one of the biggest drags on the economy as young adults find they can’t afford both mortgage and loan payments or are frozen out of the market because of bad credit, the result of defaulting on student loans.

It’s hard not to look over the border or across the water at countries who seem to have learned how to provide low or no-cost education. As reported in 2010, the average one-year cost of higher education in the United States was almost $14,000, while in Canada it was $6,000. In Europe, the U.K. had some of the highest costs at $5,300. France and Germany were both under a $1,000 and in Scandinavian countries such as Sweden, Denmark, and Norway a year of school cost around $500. A high tax burden helped subsidize costs and each country had specific population conditions, but it’s reasonable to conclude many other countries around the world place a greater emphasis on quality education, or at least providing it for as little as possible, than the U.S.

Yet the rising cost of living, demand among businesses for better educated workers, and a citizenry averse to raising taxes in order to help provide these workers is forcing state governments to get creative. In Michigan the legislature is introducing a “Pay-it-Forward” plan that will take a percentage of each graduate’s post-college income and apply it to new students. Students agreeing to the fee will pay either 2% or 4% of their income for five years for every one free year of education they receive at community colleges or state universities. If implemented, the plan would also solve the problem of interest on student loans as the percentages would be fixed and payments would only change for an individual if their income was raised or lowered.

Other states are deciding whether public dollars marked for other projects should instead go directly to higher education. Tennessee is considering diverting lottery money to fund a free community college system for any state high school graduate and Oregon is studying the costs of providing free tuition for all below a certain income level, including upgrading buildings and hiring new staff. Both states, and the other states closely watching, are counting on more money coming back in the long run from new and better jobs.

All plans have their drawbacks and doubters. Michigan’s “Pay-it-Forward” could end up costing high earners many times more the price of their education and these earners could end up subsidizing students in fields with low wages, creating a disincentive to join the program. In Mississippi, the state legislature so far has voted down any attempt to move more public dollars towards higher education, and other states could follow. A state community college or university system could become imbalanced and overburdened if too much money goes one way or another. And, ultimately, public dollars are scarce and trust in government to solve issues such as healthcare or education is at a low ebb, especially if raising taxes is part of the pitch.

But more and more students facing years of loan payments and no guarantee of good jobs seems to be forcing states to look for new solutions.

By Andrew Elfenbein

Source