Around the year 1800, the population of the entire world finally reached 1 billion for the first time in history. The two centuries that followed proved to be a time of breakneck population growth, fueled by both the Industrial Revolution and major breakthroughs in public health that reduced the death rate from a number of infectious diseases.

One scientist, however, thinks that the roots of this population growth go back 2,000 years, to the time of the Roman Empire. According to Aaron Stutz, associate professor of anthropology at Emory University’s Oxford College, it was thanks to the Roman Empire that some societies reached a watershed of political and economic organization that has had a lasting impact on the present.

Stutz draws heavily on the idea, advanced by mathematical biologist Joel E. Cohen of Rockefeller University, that the growth of human populations is profoundly influenced by social network organization. The essence of this model is that beyond the material resources available to a given population, the way in which that population is constructed as a society strongly influences how large it can grow.

Between 1,500-2,000 years ago, Stutz says, some societies reached an important tipping point for the organization of economies of scale. As a result, their populations burgeoned. The Roman Empire is Stutz’s classic example, renowned for its prosperity and its sophisticated organization.

The idea that the Roman Empire represented a new height for civilization, at least in the West, is certainly not unique to Stutz. In Why the West Rules—for Now, archaeologist and historian Ian Morris presents an index of social development based on the four dimensions of energy capture, urbanization, information processing and war-making.

For Morris, the Roman Empire reached a historically high mark on this index. The city of Rome itself reached 1 million inhabitants in the 1st century BCE. After the triumphant Octavian ended Rome’s disastrous civil wars in 30 BCE and set himself up as Caesar Augustus, the republic-turned-empire prospered.

The triumph of Octavian secured the Pax Romana, the Roman Peace of 30 BCE-180 CE, quite arguably one of the most accomplished and prosperous eras in the entire history of Western civilization. In the aftermath of Rome’s wars of conquest, the peace and security that the empire brought caused a massive increase in agricultural productivity. Not only were more lands put under cultivation, but farmers throughout the Roman Empire also invested in more irrigation and drainage systems, larger labor forces and more fertilizer.

To be sure, the benefits of the Pax Romana were distributed extremely unevenly. The prosperity of Roman society was underwritten, to an enormous degree, by the toil of slaves and low-class workers. Still, as Morris explains, not only was the overall population larger than at any previous time in history, but on the whole people also enjoyed better nutrition, longer lives and more material prosperity.

Around 500 BCE, the areas that would later become the Roman Empire’s western provinces had populations that generally lived at near-subsistence levels. Under the Roman Empire, populations in those same areas lived at about 50 percent above subsistence level.

Meanwhile, on the other side of Eurasia, another great world-empire also created an era of relative peace and plenty. What Rome was to the Mediterranean and some of the lands beyond, the Qin and Han dynasties were to China. Starting in the 4th century BCE, the aggressive and well-organized Qin Dynasty launched a series of brutal wars for empire. One by one, the fractious and divided states of what is now northern China fell.

Finally, in 221 BCE, King Zheng of the Qin crushed the last Chinese kingdom to stand against him and proclaimed himself Shihuangdi, or August First Emperor. China, it seemed, had gotten its Augustus and its imperial peace almost two centuries before Rome. Shihuangdi is remembered as the builder of China’s Great Wall, and for the enormous Terracotta Army, the collection of over 6,000 life-size clay soldiers buried with him. Fittingly enough, the English name “China” comes from Qin.

However, the Qin Dynasty did not long survive the death of Shihuangdi in 210 BCE. After several years of terrible civil war, the former Qin state was taken over by a warlord named Liu Bang, a former peasant. Liu Bang proclaimed the Han Dynasty and an era of universal peace—after beheading 80,000 prisoners of war. He would eventually take the name Gaodi, or High Emperor.

Gaodi’s triumph was made possible by compromise: he cut deals with 10 other warlords, allowing them to reign as vassal kings beneath him. Collectively, these vassal kingdoms comprised about two-thirds of the total area under Han control. It took another hundred years for Gaodi’s successors to complete his work, progressively dismantling these vassal states and bringing them under central rule.

Taken together, the considerable accomplishments of the Qin and Han dynasties proved the making of China. As with the Roman Empire, imperial rule brought peace and prosperity. Archaeological and historical evidence indicates that much as with the lands under the Roman Empire, agricultural productivity rose under the Han.

The transformations wrought by Rome and China both had tremendous implications for the diverse peoples who inhabited the vast sweep of the lands between them, from Central Europe to Central Asia and Mongolia. Indeed, similar artifacts have been found in archaeological sites from Ukraine to Mongolia, on opposite ends of the Great Eurasian Steppe.

Roman trade and military pressures drew the so-called barbarian peoples living beyond the frontiers on the Rhine and Danube into networks of exchange with the empire. These barbarian peoples responded by becoming more organized, a move that served several interrelated functions: it helped them to better protect themselves from Roman armies, enabled them to be more effective in raiding Roman lands and helped them to exert control over the flow of trade across the frontier.

For all of these reasons, smaller tribes led by military and religious leaders gave way to tribal confederations ruled by kings, such as the Alemanni, Marcomanni, Franks, and a number of others. Ultimately, the trend toward increased organization among these mostly Germanic peoples living beyond the Rhine and Danube would prove the source of tremendous challenges to Roman power.

Han China’s single greatest foreign policy challenge was the Xiongnu. Originally a collection of distinct and independent nomadic tribes living in the steppe country to the north of China, primarily in what is now Mongolia, the Xiongnu unified to create a kind of nomadic empire in the very late 3rd century BCE. Their reasons for unification paralleled those of the European barbarians vis-à-vis Rome: it enabled them to better defend themselves against China, exploit opportunities for raiding more fully, and better control the flow of goods across the frontier.

After the death of the Qin emperor Shihuangdi, the Xiongnu took advantage of China’s civil war by launching a series of devastating raids. Han emperors tried a range of policy options against the Xiongnu, from trying to crush them militarily to paying them tribute, effectively bribing them not to attack. In the 1st century CE, a Xiongnu schism allowed China to back one of the two hostile parties. Han China settled its new Xiongnu allies in lands south of the Gobi and provided them with support in exchange for their military service against their own estranged brethren. In effect, China converted its own northern frontier into a fluid borderland, giving the new Southern Xiongnu considerable autonomy in running their own affairs.

There is a profound sense in which the forces unleashed by Roman and Qin-Han Chinese development ultimately proved the ruination of their respective world orders. Trade brought more than goods and people: it also brought epidemic diseases, which seem to have become more common in both empires from about the late 2nd century CE on.

The increasingly intimate engagements between both empires and their respective barbarians would ultimately play crucial roles in their respective downfalls. In China, a farming and herding people called the Qiang began to encroach on the empire’s dominions in the west from about the 2nd century CE on. By about 150 CE or so, the Southern Xiongnu were largely left to their own devices.

Still, by this point the Han Empire was a shadow of its former self. Internal struggles between various nobles, and between nobles and the emperor, proved its undoing. China was briefly reunited by the Jin Dynasty in 280 CE, only to collapse again in the early 4th century CE. While northern China became a battleground, Chinese nobles and settlers who fled south to the Yangzi Valley both expanded the zone of Chinese culture and laid the foundations for a new economic boom.

In the case of the Roman Empire, it was the arrival of the Huns in the 370s CE that would prove decisive and disastrous. Invaders from the steppe, the Huns drove an assortment of other “barbarian” peoples into the Roman Empire as refugees. These refugees ultimately became conquerors, undoing the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE.

Although the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire survived and even rebounded in the late 5th century, in 541 CE the bubonic plague broke out from the Egyptian city of Pelusium, on the Nile Delta. It spread across the Byzantine Empire and its Sassanid Persian rival, and also swept into Western Europe. This event, rather than the earlier collapse of the Western Roman Empire, arguably marks the end of antiquity in the West.

By 541, however, China was already heading toward an imperial revival. The 6th century was a time of conflict in northern China, but the conflict led to a strengthening of governmental institutions. In 581 CE the new Sui Dynasty was founded, and soon thereafter Sui armies conquered the south.

While the fortunes of East and West diverged sharply in the 6th century CE, they both had something important in common as well. Despite the precipitous collapses of both the Roman and Han empires, both the West and the East would continue the trend toward increased population and social development.

Globally, population nearly doubled during the period from about 900-1300 CE, and the deciding factor seems to have been economies of scale. Although the catastrophes that wrecked both empires brought ruin aplenty, they did not entirely undo everything that had been achieved.

In China the trend was more obvious: the short-lived Sui Dynasty and its successor the Tang Dynasty presided over a period of rising social development. In the 10th and 11th centuries China would achieve even greater development under the Song Dynasty, and would even come remarkably close to a kind of industrial revolution.

Although the process was much rockier in the West, Stutz’s data indicate that not even the fall of the Roman Empire in the West or the collapse of the Byzantine Empire not long after could undo the trend. In the former Roman lands of both Christian Europe and the Islamic world, population growth and development continued.

There is reason, then, to believe that the foundations of the modern global population boom were laid down long before the Industrial Revolution that started in 18th-century Britain. Changes in social development wrought by the Roman Empire in the greater Mediterranean and by the Qin and Han dynasties in China would prove to have lasting consequences for the West, the East, and ultimately the rest.

Commentary by Michael Schultheiss, Editor-in-Chief

See also:

Sources:

Ian Morris, Why the West Rules—for Now: The Patterns of History and What They Reveal About the Future (Kindle)

Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians (Kindle)

William Rosen, Justinian’s Flea: The First Great Plague and the End of the Roman Empire (Kindle)

Peter Turchin, War and Peace and War: The Rise and Fall of Empires (print source)

Image credits:

Photo of Augustus of Prima Porta by Till Niermann

Image of Qin Shihuangdi public domain

Photo of Colosseum by David Iliff

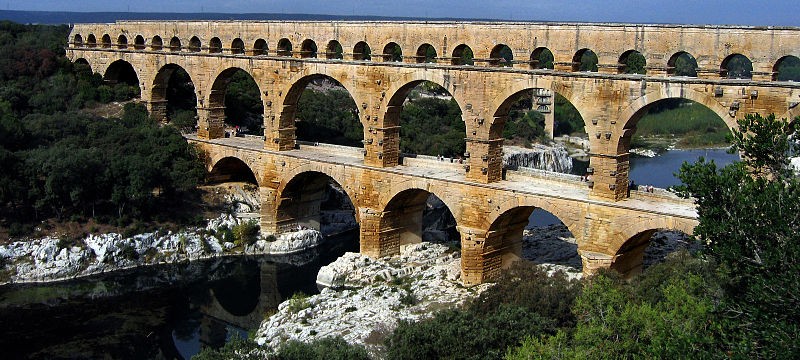

Photo of Pont du Gard Aqueduct by Emanuele

Photo of terracotta soldier and horse by Robin Chen